We’re now in the second to last month of 2020. The bulk of fashion shows have come and passed. It goes without saying that this year has been strenuous beyond words for many brands and businesses in and out of the fashion industry – some of which have shuttered under the weight of the global coronavirus pandemic and its chain reactions.

Thousands of questions remain unanswered as the search for a vaccine continues and the world is hard-pressed to persevere in any way we can as life goes on. One vital question that demands a response from designers and decision makers is this: Is Fashion Week still relevant?

Whilst proponents of sustainability, egalitarianism and digitalisation will be quick to argue against the case, it’s only fair to consider both sides of the coin. To do so, we look back on the origins of Fashion Week, its disharmony in today’s climate and how brands are adapting to new formats.

A brief history of Fashion Week

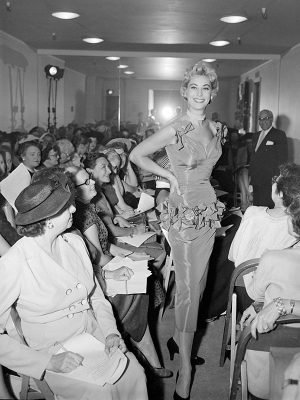

For clarity, Fashion Week is here defined as a series of fashion shows that are clustered seasonally. Its roots are often traced back to Paris in the 1800s, when The House of Worth initiated the first fashion show. Charles Frederick Worth, its founder, is believed to be one of the pioneers who employed women to wear his designs.

These salon shows, or “défilés de mode” as they were called in Paris even until today, involved a fashion parade where models would be introduced with a number corresponding to the design they were wearing. Only VIP clientele had access to these shows, which were held within the couture houses.

Several decades later, America had its first fashion show in 1903 thanks to the now forgotten New York City departmental store Ehrich Brothers. By the 1920s, fashion shows had become mainstream, though still held independently.

The true start of Fashion Week, then, can be linked to one fashion publicist Eleanor Lambert, who came up with the idea to cluster these shows to boost American fashion during the occupation of France. She invited media to attend the “New York Press Week”, which gave birth to the Fashion Week we know today.

From then on, Milan became the second city to establish a Fashion Week in 1958, followed by Paris in 1973 and London in 1984. Thus how the Fashion Weeks in the “Big Four” cities came to be, before other capitals around the globe jumped on the bandwagon.

Why is the old Fashion Week dying?

Given the long-standing history of Fashion Week – which one might note has survived World War II and the dawn of the Internet – will it outlive the latest global phenomenon to plague this generation: COVID-19? It’s a tough call, but we’ll hazard a yes – though not in its traditional format.

Before we get to that, let’s consider why it’s under fire in the first place.

Arguably the greatest crusade against Fashion Week concerns its damage to the environment. According to fashion tech company ORDRE, the industry emits roughly 241,000 tonnes of carbon dioxide per year solely through travels to the four fashion capitals for Fashion Week. This is equivalent to the electricity used by 42,000 homes for a whole year. And that’s before factoring in garment manufacture and the models, press and staff working behind-the-scenes to make Fashion Week a grand spectacle.

Then there’s the irony of Fashion Week being “old-fashioned”. In an age where almost everything is accessible at the tip of our fingers, why the need to expend countless hours and capital on shows that last only for a quarter of the year?

Separately, there have also been brands staging shows outside of Fashion Week. Alexander Wang, Gucci, Michael Kors and Saint Laurent are amongst those that have announced either a step back or a total departure from the conventional fashion calendar. These brands aren’t the first to make a change, nor are these disputes anything new; but the downtime and inevitable industry shifts following the coronavirus served as a wake-up call for all.

How can brands adapt?

Nevertheless, it’s important to acknowledge the importance and influence Fashion Week holds. For some brands and designers, especially underdogs, Fashion Week is the place and time for them to prove their worth. It offers a platform for them to engage directly with consumers and the media to garner greater publicity and recognition around the world.

While digital presentations and campaigns may work to that effect, it lacks the personal touch that fashion mavens and show regulars desire. As more and more brands go virtual, it’ll prove difficult to capture and retain the attention of an online audience. There’s still insufficient data available as to the carbon footprint of digital exercises where sustainability is concerned, too.

All things considered, perhaps the best solution forward is balance. Here are some positive cues on how to adapt to the new Fashion Week:

Merge men’s and women’s shows

Earlier in April, London Fashion Week announced that it would go digital and genderless, at least until June 2021. This opens the doors of accessibility to the larger public, while generating less waste with a more streamlined schedule.

Promote carbon neutral runways

Gabriela Hearst was the first to debut a carbon-neutral runway for the SS20 season, followed closely by Gucci and Burberry. If more brands keep, this could help reduce fashion’s impact on the planet.

Show collections at the appropriate seasons

As Dries Van Noten suggested in his open letter to the industry, it’s time to put Autumn/Winter runways back in winter (August/January) and Spring/Summer runways back in summer (February/July). Slowing down the pace ensures more balanced deliveries while preserving the perception of novelty.

At the end of the day, Fashion Week, in itself, isn’t really the problem. It’s how Fashion Week is executed and how we, as consumers, respond that makes the biggest difference.

Fashion shows are so passé: Here are the new trends narrating luxury fashion

Digitalise or die. The far-flung destination location to backdrop the presentation. The breathtaking transformation of venues to reflect the theme. The dizzying number of pieces in collections that in themselves are beginning to increase beyond track. From Chanel to Dior…

Is sustainability the new fashion trend?

Here’s how the world’s top fashion brands are weighing in. With reports of Burberry pledging to eliminate the use of plastic surfacing earlier this week, the subject of sustainability in the fashion industry continues to spark discussion. For the longest…

Featured image: Chanel SS21 show