While tattoos today are commonly worn as a way of self expression and personal identity, this form of body art has existed in various cultures since antiquity. For these cultures and communities, tattoos have been a permanent mark for different purposes – from rites of passage to symbols of protection and good fortune.

Most of these styles and traditions continue to stand the test of time, and have even become permanent souvenirs for travellers who have a desire to explore and understand these different cultures. Here are 6 unique and traditional tattoo styles from all around the world to help get you started.

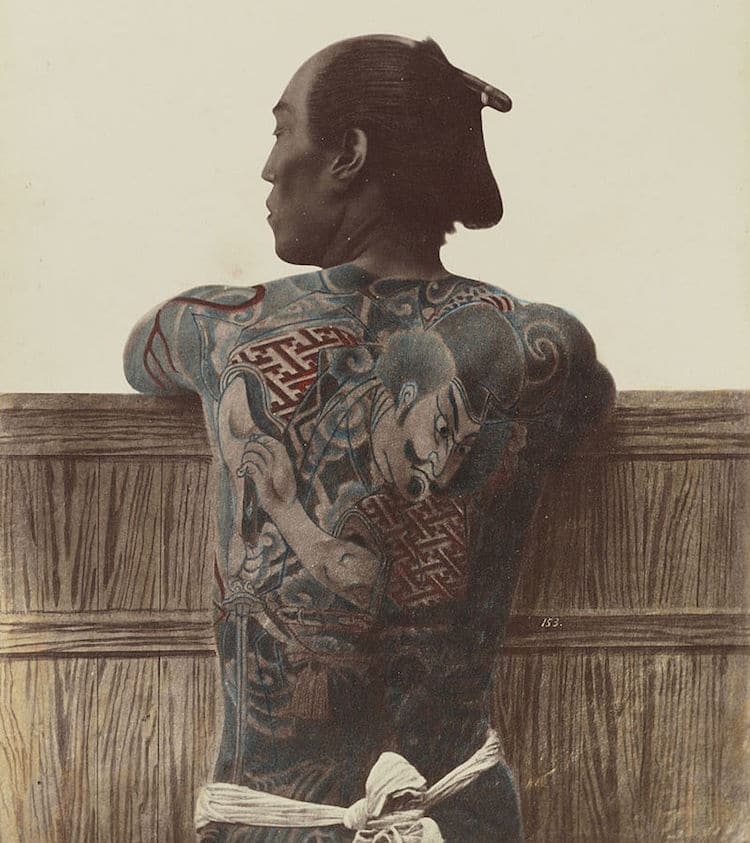

Irezumi – Japan

In Japan, the word for tattoo is Irezumi, which directly translates to “inserting ink”. While it’s commonly used as a reference to a distinctive style of Japanese tattoos, it’s also used as an umbrella term to describe various Japanese tattoo styles, including traditions from the Ryukyuan and Ainu people. Tattoos in Japan initially were believed to have been done for spiritual or decorative purposes, or as a status symbol, however in the Kofun period (300-600 AD), tattoos began to bear negative connotations, and were used on criminals as punishment.

Irezumi really developed in the Edo period (1600 – 1868), and soared in popularity in 1757 onwards following the successful release of a popular Chinese novel in Japan called Suikoden. The book was illustrated with beautiful woodblock prints that showed the bodies of men adorned with mythical beasts, flowers, tigers, and religious imagery. It then spurred a demand for these types of tattoos.

However, Irezumi was outlawed in the Meiji period, when the Japanese government wished to protect its international image, once again placing negative, criminal connotations on tattoos. This connection led to yakuza members traditionally wearing their tattoos on parts of the body that can be hidden by clothing. Despite the rising popularity in tattoos today, it is still stigmatised throughout most of Japan. Regardless, the art style continues to be widely admired, bearing traditional designs such as the koi fish to symbolise good luck and fortune; the dragon to represent protection, wisdom and strength; and the snake as an embodiment of regeneration and good health.

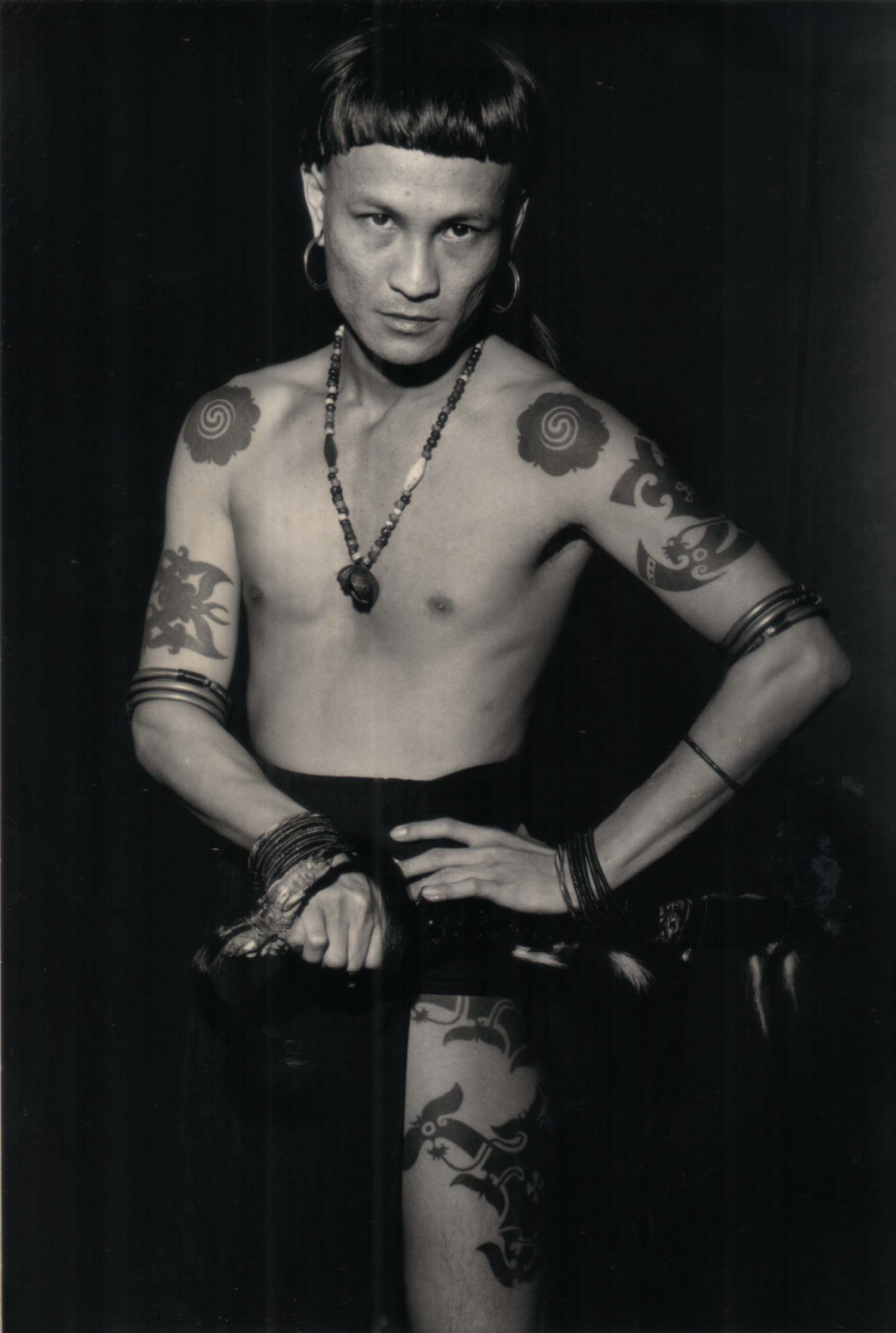

Iban Tattoos – Sarawak

In Sarawak, tribal tattoos are a crucial part of the Iban culture, done as a symbol of protection, status symbol, or to signify certain events and experiences in the bearer’s life. Some motifs include marine creatures such as the crab (ketam), the crayfish (rengguang) and the prawn (undang), while others take on more ferocious creatures such as the cobra (tedong), ghost dog (pasun) or dragon (naga).

The most well-known and significant motif of traditional Iban tattoos is the Bunga Terung, or eggplant flower, which is believed to signify new beginnings. It’s traditionally tattooed on both sides of the shoulders of a young man prior to his rite of passage, where he would journey solo into the jungle to fulfil a specific task – such as his first kill on a hunt. The tattoo is thought to bestow strength and bravery to the bearer. The coil in the middle of the tattoo is meant to represent the underbelly of a tadpole, which also signifies the bearer’s readiness to begin a new life as a grown man.

Tā Moko – New Zealand

Probably one of the most popular tattoos is the highly sacred Tā Moko, the traditional tattoos of New Zealand’s indigenous people, the Māori. Done as a rite of passage starting from adolescence, their tattoos are usually made up of a combination of lines, whorls, and natural motifs that bear ancestral messages, visual stories, and details specific to the wearer. For example, the unaunahi, or fish scales pattern, symbolises abundance and good health. A traditional good luck charm of the Māori, the hei-tiki may also be tattooed as a symbol of good luck and protection. Since traditional Tā Moko is so personal to the wearer, each tattoo is one of a kind, displaying the unique stories of that person, as well as the fine craftsmanship and the Māori culture.

Tāo Moko can be done on parts of the body such as the back, shoulders, arms, and legs, however the most popular kind is the facial tattoo, as the head is considered the most sacred part of the body. Facial tattoos often symbolise the rank, social status, and prestige of the wearer.

Today, while Polynesian tattoos are widely popular, these cannot be considered as Moko – as that is strictly reserved for Māori people and tattoers. For tattoos on non-Māori tattooers and wearers, the style is called Kirituhi, as it does not bear the same cultural significance as the Moko. Traditional Tā Moko tattooers are also called tohunga-tā-moko, who are considered tapu, meaning highly sacred.

Sak Yant – Southeast Asia

Yantra tattoing, also known as Sak Yuant or Sak Yant, is a style that consists of sacred geometrical, animal, and deity designs that can be done in Cambodia, Laos, Thailand, Indonesia, Philippines, and parts of Myanmar. Yantra tattoos are also accompanied by Pali scripts, which are believed to bestow mystical powers of protection or good luck on the wearer – so long as the bearer also observes certain rules and taboos such as abstaining from a specific kind of food. These tattoos are usually practised by ruesi or rishi, wicha practitioners, and Buddhist monks. A metal rod with a sharpened point called a khem sak or a bamboo rod called mai sak is dipped in ink and then hand-jabbed into the flesh to create the tattoo.

It’s also believed that the power of the Sak Yant tattoos eventually decrease with time, so in order to “re-power” them every year, bearers will celebrate with their Sak Yant masters in a Wai Khru ritual, meaning “to pay homage to one’s guru”.

Ptasan – Taiwan

While the more brutal traditions of Taiwan’s indigenous Atayal (or Tayal) people such as headhunting are no longer practised, one tradition that they wish to preserve is their art of facial tattooing. Known as ptasan, these facial tattoos are part of coming-of-age initiation rituals, that were done on both men and women after they had performed a major task associated with adulthood.

For the man, he would have to show his valour as a hunter and protector by taking the head of an enemy, while the woman would have to master the skill of weaving and cultivating. Only those bearing the facial tattoos are allowed to marry, and it is believed that after death, only those with tattoos could cross the spirit bridge, or hongu utux into the afterlife. The men usually would sport simple designs, such as two bands down the forehead and chin, while the women wore far more intricate designs from one ear – across both cheeks to the lips – to the other ear. The tools include the atok – an instrument featuring a group of four to sixteen needles are attached to a stick; it is then used to tap the ihoh ink – made from charred pinewood resin – into the skin using a “hammer” called a totsin.

Mehndi – India

While mehndi is actually commonly practised in Malaysia, it’s often confused with henna, which is actually the paste used to create the temporary body art. Mehndi has been practised for thousands of years, in countries such as India, Bangladesh, Nepal, Pakistan, and the Maldives. Traditionally, mehndi is applied during Hindu, Muslim, and Sikh weddings as part of a beautification ritual, as well as on special festivals such as Diwali, Teej, Bhai Dooj, Aidilfitri, and Eid-al-Adha.

Mehndi is applied to the skin out of a plastic cone, with a paintbrush, or a stick. Designs can range from floral and natural motifs to geometric shapes. After the henna paste has dried, it will begin to crack and leave behind the stain. At this time, a mixture of lemon juice and white sugar may be applied to the design to darken the stain, which will typically last up to two weeks. The final colour is usually reddish brown, and while other colours such as white, red, gold, or black may be used, these are not usually made from natural ingredients and may be unsafe. Thanks to its temporary nature and intricate design, mehndi continues to be a popular form of body art. Mehndi kits can easily be found in Indian stores or hobby shops all around the world or online, and tourists often get mehndi done on their hands as a souvenir from a trip in South or Southeast Asia.