Vinesh Sinha has been championing the waste oil industry for nearly a decade with FatHopes Energy, but there’s a bigger vision he wants to bring to fruition now: Economy 2.0.

The day before our interview, Vinesh Sinha had met with the Prime Minister of Malaysia Tun Dr. Mahathir Mohamad.

“When I grow up, I want to be like him,” the founder and CEO of FatHopes Energy posted on Facebook after the keynote meeting.

It is understandable (“he’s an amazing leader and it’s incredible to see how he does what he does at his age”) yet curious for the 31-year-old entrepreneur to have said that, given how he describes a younger version of himself as delinquent, naïve and reckless.

But it was precisely the sum of his delinquent, naïve and reckless decisions that has earned him the pride of establishing a multimillion-dollar biodiesel company and a spot on the esteemed Forbes 30 Under 30 Asia 2018 list.

Playing with fire

Vinesh first discovered biodiesel (though he hadn’t realised what it was then) after watching Jeremy Clarkson fuel a red diesel Mercedes with used cooking oil in an episode of TopGear.

“At the time, I was going to an international school and everyone who had a licence got a nice, fancy European sedan but I didn’t. I was given a diesel vehicle which I was not very happy about. It was an old Mitsubishi Pajero,” he recollects of his 17-year-old self during our interview.

Jealous and frustrated, he thought he would replicate what he learnt from Clarkson to save some pocket money…or worse (better), ruin the car (and get a new one). It worked for a day, but landed him at the workshop the next morning, trying to figure out why his car wouldn’t start.

“The reality of ruining the car actually came into fruition for me, so be careful what you wish for,” he says, half-jokingly. “But I realised it was not really what I wanted, it was just the delinquent in me that was hoping for the worst. If I had a brand new vehicle, I probably would not have tried it.”

“I believe in the saying that the universe conspires with you when you know what you want, but you need to know what you want.”

Fortunately for him, the problem was not unsalvageable. He single-handedly flushed out the food waste from the car engine for it to run again and even found an alternative effective blend to fuel the vehicle. The latter was achieved by heating used cooking oil over the stove, filtering it with an old T-shirt and mixing it with equal parts diesel.

Unbeknownst to his parents, he continued producing the diesel substitute for himself and a few close friends. But it wasn’t until he went to the UK to study Business and Finance a year later that he actually understood its potential.

“When I arrived in the UK, I was exposed to biodiesel at the petrol station and the question that arose was ‘what’s biodiesel?’. I didn’t realise that was what I was doing, so the dots were not connected for me,” he divulges.

“Three months later, on the front page of the newspaper, there was an introduction of a 30 pence home brew fuel tax – that was really the acceleration factor for me. This had to be happening on a sizeable scale for the government to want to put a tax on it.”

Oil trade waste for wealth

The year was 2006 and his epiphany had led to further research, enlightening him on the fact that biofuel had been widely used in the UK for years.

“Just to be clear, biodiesel can be produced from any oil, new or used, as long as it’s organic,” Vinesh explains, “I thought that waste oil would be the best because it would be the lowest barrier for entry, so I started volunteering in small biodiesel plants that were converting used cooking oil to sell.”

His volunteering stint came at the cost of skipping classes in university, but the tradeoff was the exposure to all levels of the supply chain. It was a no-brainer.

“Being young and naïve, you never really weigh your options. At that time, it was more of what I wake up and feel motivated to do… The fact that I could get down and dirty with my hands from the start all the way to the end (of the supply chain) gave me a very high level of fulfilment,” he regales.

“The main reason we do what we do is because we want to leave the planet a better place than when we joined it.”

In 2009, he was offered a contract to sell biofuel to a logistics company that was seeking to achieve a green fleet. Without pausing to consult anyone, he said yes.

The next few steps involved writing to his university to ask for a refund; using the money to buy a small biodiesel plant from one of the companies he volunteered at; and buying a ticket back to Malaysia to do just that.

“If it was one year later, I probably would not have had enough money to buy the plant, so it was really the right time, right place and right opportunity – that’s the beauty of life. That’s why I believe in the saying that the universe conspires with you when you know what you want, but you need to know what you want,” he reveals.

And what he wanted was to monetise and scale up his hobby of converting waste oil into biodiesel, even if that meant dropping out of university (and facing “emotional warfare” with his family as a consequence). Does he have any regrets?

“None at all. It was the best thing I ever did in my life,” he says simply.

Greasing the wheels of the business

After running a one-man show of sourcing waste oil from eateries and converting it into biodiesel for close to a year, Vinesh founded FatHopes Energy in 2010.

“For the first few years, it was extremely challenging because of the question of stability and my persona doesn’t really depict that,” he says unreservedly. “Businessmen here are not comfortable working with young people internally – finding staff that will tow the line and who had experience, which meant people older than me – as well as externally.”

“It’s not a very glamourous business, but giving people a good understanding of what we do changes their perspective. The main reason we do what we do is because we want to leave the planet a better place than when we joined it,” he adds.

Today, FatHopes has over 35,000 points of waste oil collection across Malaysia and Singapore. It yields commercial volumes of feedstock consistently, all of which are exported to European gas and oil companies. Factories account for the largest volume contribution to the entire feedstock, although fast food chains like McDonald’s and KFC make for more recognisable partners.

“The waste oil industry has the potential of substituting close to 25 percent of global liquid fuel energy demand and we’re just on the tip of the iceberg of that.”

To maintain an upper hand over competitors, it regards feedstock suppliers as monetisation partners rather than a buyer-seller relationship. Their FHE iTank technology (which allows eateries to dispose of used cooking oil directly into the tank to be collected once full) is one sign of commitment to a long-term partnership and return on investment.

Data collected from the proprietary tank technology enables FatHopes to reduce its logistics cost and at the same time, offer better accountability and traceability to vendors who can now look at waste oil management as a stream of revenue. This, in turn, curbs various forms of environmental pollution.

The company also emphasises on R&D, or what it calls ‘dicovery units’. These units set out to identify waste generated from human habits and how to maximise it for the biofuel industry.

“I believe that you don’t know what you don’t know, and when you discover what you don’t know, there’s endless opportunity there. We are feedstock agnostic, so as long as it’s waste and useable for biofuel, we’ll go get it. We have discovered about 30 raw materials and work with about 8 to 10 on a commercial scale,” he says.

It all forms a bigger picture that is waste wealth, which he attributes as the cornerstone of what he calls ‘Economy 2.0’.

Fuelling the road to economy 2.0

“In every dollar that we spend, a certain percentage of that dollar has either been externalised because the waste materials that was produced thereafter and the impact it has caused was not accounted for; or used to bring that product to society,” Vinesh expounds on the context behind the term.

“Economy 2.0 will re-internalise those cost factors so that there is a true value on our decision, and then maybe we will change our decisions because it will become too expensive to act the way we’re acting.”

After all, he postulates that a company that is good for the society and the environment should make more money than a company that is polluting.

This had been the point of discussion during his appointment with the country’s premier, and just as we approach the end of our interview, he tells us he’s got called into the Prime Minister’s office again.

“We’re trying to propagate the whole idea of recovering and maximising the monetisation potential of waste residue and by-products of the nation on a national scale and the new government is relatively enthusiastic and supportive,” he lets on.

“The waste oil industry has the potential of substituting close to 25 percent of global liquid fuel energy demand and we’re just on the tip of the iceberg of that. With Malaysia being a manufacturing hub and export-centric economy, it’s a good springboard for us to start – as we have already done ten years ago – and to scale regionally.”

His vision is to expand FatHopes across Asia and Australia by 2022, and the company is already poised to cover Thailand and Indonesia by the end of the year.

Before he rushes off to Putrajaya, we squeeze in one more question on what he considers his personal greatest achievement.

“I recently came back to the office after a long break and a staff came to me and said ‘the sound of your voice gives us hope’. To me, my greatest achievement is really in giving hope to the immediate circle around me and to the next circle beyond them. The only way, I believe, I can achieve that is through small wins, consistently,” he says with his signature grin.

With ‘FatHopes’ such as his, we won’t be surprised if someone looks at him now and says “when I grow up, I want to be like him”.

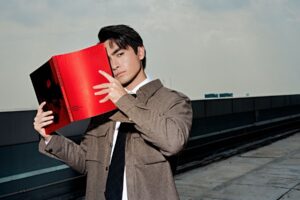

Photography: Ian Wong

Art direction and styling: Gan Yew Chin

Grooming: Ling Chong

Special mention: Vinesh wears the Longines Evidenza watch in the featured image