She’s unwaveringly faced some of the world’s greatest competition on court but Goh Liu Ying’s biggest hurdle now lies in finding who she is off it.

Hardly a Malaysian is unfamiliar with Goh Liu Ying’s name following the fateful date of August 17, 2016.

We cheered, we cried, we couldn’t be prouder when she, along with her badminton partner Chan Peng Soon, made history by clinching the silver medal in the mixed doubles badminton event at the 2016 Summer Olympics in Rio de Janeiro. They beat China’s Zhang Nan and Zhao Yunlei in the semis and put up a good and solid fight against Indonesia’s Tontowi Ahmad and Liliyana Natsir in the finals to become the first mixed doubles team from Malaysia to stand on the podium.

They gave us an unprecedented silver medal that would bring the total medal count to five that year, a record number of wins at the prestigious event.

“My entire family never imagined I would be an Olympic medalist,” tells the soft-spoken lanky 28-year-old. “We were the underdogs all along so it didn’t matter if we won or lost. We had already triumphed above our previous achievement.”

Charting history

Thrown into the world of racquets and courts since she was as young as three by her father who loves the game, Goh insists the sport chose her instead of the other way round.

“Up until I was 16, I was the worst performer and was often ranked the lowest in my team,” divulges the Bukit Jalil Sports School graduate. “I don’t know why I stayed, but I never thought of quitting either.”

A switch to the mixed doubles category on the recommendation of her then coach Rexy Manaiki marked a turn-around for her.

As Malaysia’s first mixed doubles pair, she and Chan lighted a blazing path through the mixed doubles categories in championships like the Asian Badminton Championships as well as a host of Superseries titles. They went on to qualify for the 2012 Olympics in London – Goh’s first introduction to the arena – before the historic match in 2016.

“Many people perhaps don’t remember us from 2012 because the mixed doubles isn’t a hot event,” she says matter-of-factly. “But that’s one thing I’m hoping to change by letting our achievements speak for itself.”

In the face of uncertainty

Speak for itself it did.

Along with the new title and medal, Goh saw her social media following balloon overnight. People now recognised her on the streets, with some even coming up to her and asking for photographs. Our mixed doubles pair of badminton players are now as proudly spoken about as our men’s singles and doubles players.

“I’m still adjusting to getting asked for photos and stuff,” Goh admits sheepishly. “I’m very simple; I hardly dress up or doll up.”

Simple is the last word we’d use on Goh. She is quiet, driven, grounded, determined, quick to smile, but certainly not simple. Simple doesn’t describe a girl who left home at 13 to be on her own, persevered through countless rounds of ranking lowest on her team yet not give up and trading a regular childhood of hanging out with friends and weekends at the movies for gruelling training hours on court.

Simple isn’t a girl who, despite being at the prime of her life and career, fearlessly battles knee and shoulder injuries, even resorting to surgeries to remedy the above, just to be able to spend a few extra years on court, Olympic medal or otherwise.

“I want a longer badminton career so I will sacrifice this small chapter for now.”

Said surgeries are the reason why she’s made to sit out the BWF World Championships in Glasgow, as well as the 2017 SEA Games.

“I’m quite upset about the SEA Games because I’ve played in many SEA Games but never in Malaysia,” she tells. “The homeground advantage is what every athlete lives for, it’s very different.”

She glances at her knee as she says this, all taped up in elastic sports tape as we speak. She shifts almost stiffly at the mention of her shoulder. “I was back competing merely 8 months after my surgery. I wasn’t fully recovered but I was back on court because I was trying to qualify (for the Olympics in 2016).”

The surgery itself is a gamble; doctors can’t assure her that she will heal in time – if at all – and if she doesn’t, that’s the end of her career.

“I want a longer badminton career so I will sacrifice this small chapter for now,” she adds. “It’s a choice I made and I intend to stick with it.”

“Who am I off-court?”

The only other thing as persistent as her injuries are her uncertainties of her own future.

“I’m quite afraid of what I’m going to do after I retire,” she opens up. “Who am I off-court? Sports is short-lived career.”

She faces the lacklustre choices too many athletes have undoubtedly come to face – to go back to school and pick up a “safe” degree like sports science, or turn to coaching.

Then there’s the question of building her own future on the personal end.

“I’m in no rush to settle down as I’m very focused on my badminton career right now but that won’t always be the case,” she soundly admits. “My body is quite weak now too as I overexert so much. Painkillers are my regulars every month. I force myself to be better because what choice do I have?”

Yet, there is not a single day when she regrets choosing this long and strenuous athletic path.

“There’s something about the training,” she reflects. “It’s hard, but I find it character-building and definitely life-changing. There are some things I’ve missed out being an athlete, but there is so much more I’ve gained that I will not trade for anything in the world.”

Her future hangs on a match point right now as she has to sit out many championships while she heals up but this uncertainty is something she is familiar with from the get-go.

If there’s one thing she’s sure of, however, it’s the potential of the sport and its future for women players like her.

“My dream is to see women excel more in sports. Maybe after I retire I can help more girls see that it’s a possibility, that sports isn’t a man’s arena.”

She chose this path not knowing if it’ll pay off and now she sticks by it despite being just as uncertain as she was when she first formally picked up the badminton racquet at 8.

“Sports is not a business,” she reminds us. “People need to understand that sometimes there is no assured payback. There’s no certainty. You can invest a lot in one player, but they won’t yield the results you were hoping.”

“Maybe out of a hundred potential players you train, one is a star,” she adds. “That one is all you need.”

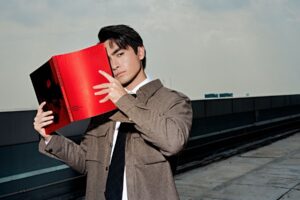

Photography: Ian Wong from The Home Studio

Videography: Zac Lam

Art direction: Yew Chin Gan

Styling: Yew Chin Gan

Hair and makeup: Gavin Soh

Special mention: Goh Liu Ying wears jacket by Bottega Veneta, earrings by Kate Spade New York and a Cartier Juste un Clou ring in the featured photo