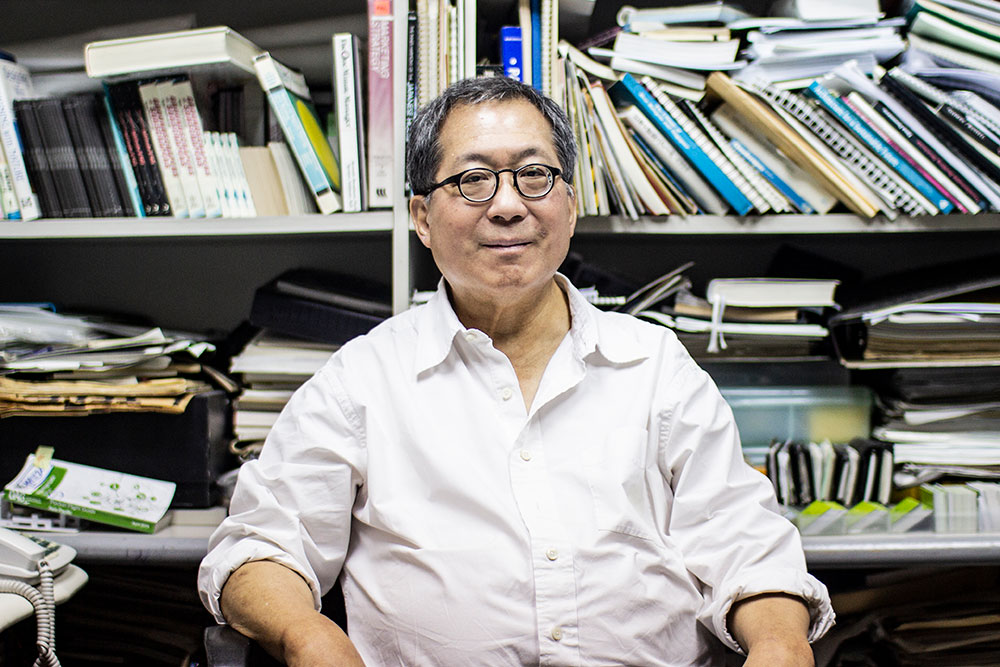

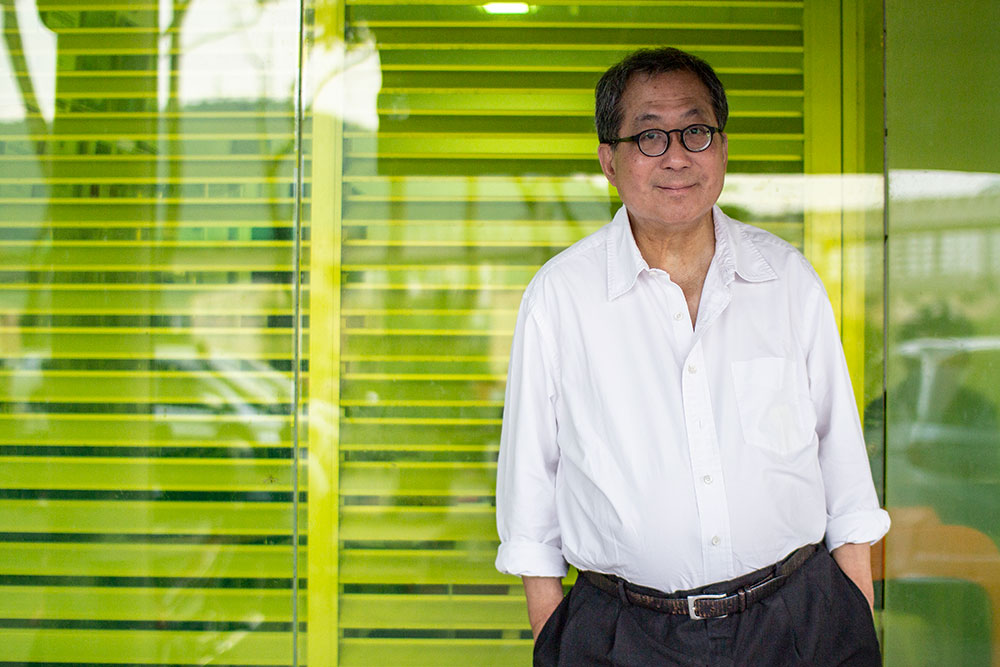

Despite close to 50 years of hard work, Dr Ken Yeang will stop at nothing to save the planet through the advancement of ecological architecture.

Most people would consider 71 a ripe age for retirement. But Dr Ken Yeang is far from taking a back seat at the architectural firm he established with his partner, T. R. Hamzah & Yeang.

That’s not to imply that the revered Malaysian ecologist, architect and author is a workaholic; on the contrary, he starts off our interview in a tone of weariness – which one may almost interpret as regret.

“If I had to start life again, I wouldn’t be an architect. It’s a dismal life. I work until 3 o’clock every day,” he groans in the middle of what appeared to be another gruelling day at the office.

At the baffled look on our faces, he explains, “I wanted to be a graphic designer or an artist but my father was a doctor, so he told me to be a doctor or do something that’s equivalent. I compromised and decided to be an architect.”

Ecology versus architecture

Several years into his parent-approved professional career, Ken was given the opportunity to work as a researcher on an ‘autonomous house’ project. The idea was essentially to build a house that stands by itself, disconnected from water and electricity supply.

After six months, he realised the project only focused on eco-engineering, whereas the bigger picture involved the ecological aspects of architecture. But that was in the ‘70s and the latter concept was practically unheard of then. Understandably, his proposal to his boss was met with the suggestion to pursue a doctorate for better credibility.

“So, I left and did a PhD, and my doctorate became my life’s agenda,” he deduces on the turning point of his career.

Since then, Ken’s design philosophy has been to integrate the natural environment (ecology) with the built environment (architecture).

“When you study ecology, your perception of the world changes. You don’t see yourself as the only dominant species. There are other species on the planet that have just an important role to play and every right to live as you have,” he contends.

“In architecture, you only care about people and technology. In ecology, you care about the environment,” he elaborates for contrast.

Race and rescue mission

Combining the matters of interest on both grounds, ecological architecture takes into consideration four factors: nature, technology, hydrology and people.

To provide an example, one of Ken’s pioneering designs, Menara Mesiniaga, was built with vegetation in the form of ‘sky courts’ to promote natural ventilation as wells as to connect building occupants with nature. In addition, passive solar principles such as photovoltaic panels were implemented to supplement electricity consumption and reduce the overall use of energy.

It marked the first of a series of buildings that embodies his innovation of ‘bioclimatic skyscrapers’ which maximise environmental resources to provide thermal and visual comfort to occupants.

While the tower remains one of Ken’s most distinguished designs today, much has evolved in the field of eco-architecture since its inception in 1992.

“Ten years ago, we designed in a preventive sort of way – to prevent further damage to the environment. But in the past ten, twenty years, we’ve done so much damage that it is now a race and rescue mission,” he reveals.

“There are other species on the planet that have just an important role to play and every right to live as you have.”

In response to that mission, he has progressed from passive eco-designs to two entirely different strategies. The first utilises tools like biodiversity metrics to enhance the ecological integrity of the built environment.

“We don’t just design spaces but we create habitats where different species can live in the environment. We do research on the fauna that we want to bring into the habitat and then, we add the flora to attract the fauna,” he expounds.

The second is to incorporate biodegradable materials in built systems so that when the life of a building is over, it goes back to the environment. As an extension of this strategy, he aspires to fully realise the principles of eco-mimicry, in which buildings are designed to imitate and replicate nature.

“In nature, there’s no such thing as waste. Waste is a human invention. Nature recycles everything, so why can’t we imitate nature and recycle everything? But to recycle everything, we have to make sure everything is recyclable,” he resolves.

Joy in the struggle

For there to be significant changes, however – and this applies across the globe, too – Ken believes that it has to come from a governmental level. Yes, the Green Building Index (GBI) has been one important implementation to promote sustainable architecture in Malaysia, but his observation shows that the people’s mentality has not yet evolved.

“We can change our leadership, we can change by example, but we cannot tell people you have to make green buildings because we are a service industry,” he says.

“I think my generation is difficult to change because they were brought up in a non-green way. My hope is that people will treat ecological design as a part of architecture so that the next generation of architects will do more green architecture.”

Again, there is that strain in his voice and tension between his brows that we noticed early on in the interview, and we can’t help wondering why he would still put himself through such pressure after 50 years of blood, sweat and tears in the industry.

“My hope is that people will treat ecological design as a part of architecture so that the next generation of architects will do more green architecture.”

Surely, his relentless labour up until now merits repose for the remaining years of his life?

“I feel like I’m running out of time and I’m afraid I might not be able to continue my agenda,” he confides, putting things into perspective. “I’m really tired, but I’m driven to try to do something for the planet and there are still about a dozen things I want to achieve.”

And so, he pours hours each day into overseeing tens of projects whilst juggling what he calls his 4Rs – reading (a mountain of books and files sit on his table as we speak); writing (he is set to publish another book later this year); arithmethic (“I have to make sure I have enough money to pay my 80 staff and run the business”); and of course, architecture.

At the end of the day, is he happy though?

“Oh, I’m happy everyday, but the greatest joy I have is to wake up every morning wanting to set the world on fire,” he regales. “When we invent something that’s useful to people and to other architects, it gives me immense joy.”

And that’s why Dr Ken Yeang will not give up advancing the heights of eco-architecture for the betterment of the planet.

Photography: Gan Yew Chin